Americans are losing friends and family over partisan politics at alarming rates. At least, that’s what a recent Reuters/Ipsos poll suggests.

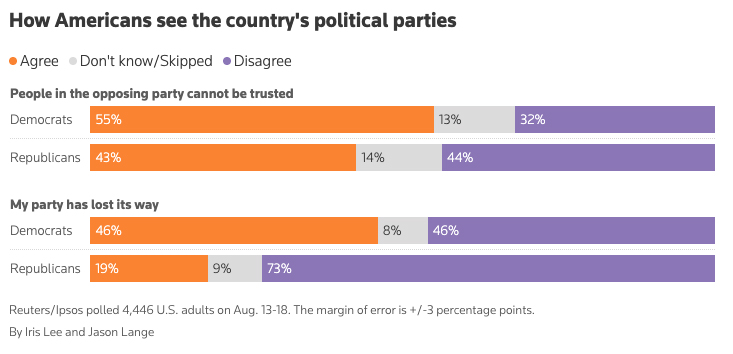

The survey, which included nearly 4,500 U.S. adults, indicates an alarming emergence of political attitudes in America. Among other things, the survey found that 27 percent of Democrats say the last presidential election damaged their friendships, compared with 10 percent of Republicans. Trust is dissolving; more than half of Democrats say Republicans cannot be trusted, while 43 percent of Republicans say the same about Democrats.

Those are big numbers. What’s behind them? And by that, we mean more than anecdotes – family tables with empty chairs, group texts gone quiet, friendships that have gone brittle.

If you can’t beat ‘em, block ‘em

While the poll doesn’t specify how friendships have been broken or who initiated the breakup, it appears progressives are feeling this conscious decoupling more deeply. The reasons seem obvious: It’s easier, and maybe even more principled, to pull away than to keep wrestling with a loved one’s toxic partisanship.

We understand the impulse. We’re trudging through a time when outrage is manufactured for clicks, when algorithms reward fury, and when corporate news outlets make billions by sharpening and amplifying our differences. That kind of sustained rage can’t help but leak into our everyday interactions. It’s exhausting, and sometimes, retreat might be the only way to preserve the peace.

But it’s worth asking: Why does it seem to be those who talk the most about tolerance and inclusion who are stepping back? Could it be that for left-leaning Americans, the 2024 election was the final straw in those relationships – relationships that likely were already strained from the past three election cycles – and they had to be the ones to make the break? Or is it the narrower nature of the president’s movement that is leading his adherents to exclude “non-believers” from their circles? Like most public opinion surveys, the numbers leave plenty to ponder.

It’s not brand-new

In March 2024, Nebraska U. scholar Elizabeth Theiss-Morse and a colleague dug into this topic in their book, Respect and Loathing in American Democracy. The research suggests that Americans overwhelmingly say respect is essential for democracy, but struggle to extend it to people they see as fundamentally different. Liberals often moralize questions of inequality and discrimination in terms of social justice as imperatives to protect vulnerable groups and ensure equitable outcomes; conservatives moralize questions of patriotism, respect for traditional institutions, and the preservation of shared national identity. Respect and common purpose can’t help but get lost in the clash.

Part of the problem, we know, is structural. In other democracies, multiple viable political parties tend to force compromise and keep the discussion on policy, not morality and existential threat. Citizens in these nations learn to listen as leaders work across differences, because no single party governs alone.

America is a unicorn among the world’s democratic societies – we’ve had a two-party system for so long, it’s hard to imagine another way. The terms Democrat and Republican each used to cover a lot of ideological ground, but now they come loaded with assumptions about a person’s entire worldview. Further research shows those assumptions are often wrong, which we wrote about earlier this summer. But it doesn’t stop us from jumping to Grand Canyon-sized conclusions.

Real connection is still possible

Connectedness often shows up in the everyday places where ideology isn’t front and center: a neighborhood cleanup, a school fundraiser, a volunteer shift, a storm that knocks out the power and sends neighbors to check on one another. These ordinary interactions don’t erase profound differences, but they’re examples of how our shared lives are bigger than partisan labels.

Connectedness often shows up in the everyday places where ideology isn’t front and center: a neighborhood cleanup, a school fundraiser, a volunteer shift, a storm that knocks out the power and sends neighbors to check on one another. These ordinary interactions don’t erase profound differences, but they’re examples of how our shared lives are bigger than partisan labels.

So if this is the case, why aren’t we talking to one another?

Maybe it’s fear. If so, then we’re reminded of the 2011 film We Bought a Zoo, of all things. Probably the most enduring thing to come from that almost-forgotten movie was the phrase “20 seconds of courage.” It was meant for matters of the heart – dispensing with pretense, taking a risk, and speaking honestly and authentically to another person.

What if we tried that in our civic lives, too? Twenty seconds to start a hard conversation. Twenty seconds to ask a question instead of changing the subject. Twenty seconds to break the silence with a neighbor or relative we’ve written off. Is that enough time to change democracy? Well, maybe not all at once. But multiplied across a community, a state, and a nation, those moments of courage could add up to something profound.

We want to be clear here: No one should be expected to cozy up to white supremacists, neo-Confederates, or anyone else who is openly committed to tearing down American democracy. Bright moral lines matter. But if our lives only include those who already agree with us, democracy shrinks into something small and brittle.

That twenty seconds of courage can lead to civic resilience. And that can lead to sticking with the book club even when politics leak into the discussion. Or asking, “What matters most to you about that?” instead of shutting the door. Or checking in on a neighbor when the weather turns bad, regardless of their party affiliation. Or however you connect daily with those in your world.

Polarization is real, and the losses are painful. But our shared civic life is more than ballots and laws. It exists in the messy, imperfect, human ties between us, which have powered our nation to preeminence over the centuries. Each time we choose to keep those ties alive, we give democracy a little more breathing room.

And maybe all that takes to start is twenty seconds.