Superman – Clark Kent, Kal-El, The Man of Steel, the Last Son of Krypton, The Big Red S – is returning to the big screen. That’s right, James Gunn’s Superman, arguably the most anticipated action movie of 2025, hits theaters on July 11. And while fans debate casting choices, the physics of certain superpowers, and whether the new suit has the right amount of nostalgic shimmer, it’s worth stepping back to ask: Who is this guy, really?

If you’re not a close follower, you might not know that America’s first and greatest superhero has lived many lives. In his nearly 90 years on our third rock from a funky yellow sun, Superman has been a New Deal strongman, a Cold War propaganda tool, a moody War on Terror-era alien, and more recently, a kind-hearted farm kid with interstellar baggage. Supes is our oldest hero and our most malleable myth; to understand him is to crack open a time capsule of 20th- and 21st-century America – spandex, idealism, and all.

This looks like a job for the Complete Patriot’s Guide!

The long road to Smallville

Before he was a national icon, Superman was an idea. For millennia, elements that would eventually combine to form the Man of Steel were scattered throughout our world’s oral histories. Gilgamesh wrestled immortality, Moses floated to safety in a basket, and Hercules cleaned up literal messes (the Augean stables, anyone?). These mythical heroes all came from somewhere else, physically or spiritually, and changed the course of human events with their strength, cunning, and moral clarity.

Before he was a national icon, Superman was an idea. For millennia, elements that would eventually combine to form the Man of Steel were scattered throughout our world’s oral histories. Gilgamesh wrestled immortality, Moses floated to safety in a basket, and Hercules cleaned up literal messes (the Augean stables, anyone?). These mythical heroes all came from somewhere else, physically or spiritually, and changed the course of human events with their strength, cunning, and moral clarity.

Even Friedrich Nietzsche, that famously misunderstood philosopher, gave us the Übermensch, a visionary not bound by conventional morality, someone who could transcend petty human squabbles and embody the next evolution of the human spirit. While bad-faith ideologues hijacked Nietzsche’s vision in the 20th century, his ideal was more poet than tyrant: someone who lifts others — not literally, but by reimagining what is possible.

You can also trace super-threads through the Jewish concept of the golem, a clay figure animated to defend the oppressed. The golem is multifaceted in Jewish culture; often, it serves as a protector formed in times of fear and persecution, and is seen as a symbol of community survival. It’s not hard to see how this blend of myth, scripture, and moral yearning could take root in the hearts and creative minds of two Jewish teens, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, in late 1930s America.

So, in a way, Superman has been with us much, much longer than the Great Depression. The various streams of human imagination were all out there: strength, outsiderness, moral purpose, and the promise to lead us all to something better. The concept just needed a little nudge to bring all the tributaries together.

Capes! Capes for the working class!

Enter Siegel and Shuster – classmates at a local high school who bonded over their love of pulp novels and science fiction – who initially envisioned a villainous psychic megalomaniac in the 1933 short story The Reign of the Super-Man. But after multiple rejections, they recast the character as a heroic figure with superhuman strength and abilities. They settled on a “Man of Tomorrow” at the peak of human evolution, which is why he once leaped over buildings in a single bound; it was a while before he flew around like a heat-seeking missile, like he does today.

Enter Siegel and Shuster – classmates at a local high school who bonded over their love of pulp novels and science fiction – who initially envisioned a villainous psychic megalomaniac in the 1933 short story The Reign of the Super-Man. But after multiple rejections, they recast the character as a heroic figure with superhuman strength and abilities. They settled on a “Man of Tomorrow” at the peak of human evolution, which is why he once leaped over buildings in a single bound; it was a while before he flew around like a heat-seeking missile, like he does today.

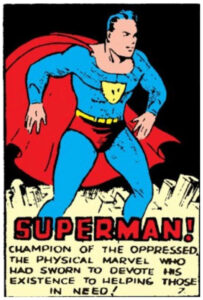

Siegel and Shuster infamously sold their creation to National Comics, the precursor to DC Comics, for just $130. In April 1938, Action Comics No. 1 hit newsstands. The story was, to put it mildly, a smash hit: Superman, a “champion of the oppressed” devoted to helping those in need, resonated deeply with Depression-era readers seeking an escape and a glimmer of hope. The issue promptly sold out of its initial print run of 200,000 copies, and today it remains the most valuable comic book on the planet. Superman coming to life was so seismic, in fact, that Action Comics No. 1 is widely considered the beginning of the superhero genre.

True to form, the early Man of Steel didn’t waste time on cosmic threats or other super-powered nemeses. In his first adventures, he foiled corrupt CEOs, gave domestic abusers a good clobbering, and yanked politicians out of their ivory towers to get their hands dirty to help the common folks. He was the bruiser for the little guy, a populist champion who backed up his tough talk, a buffed-up FDR with a more colorful tailor.

Radio, serials, and the Klan

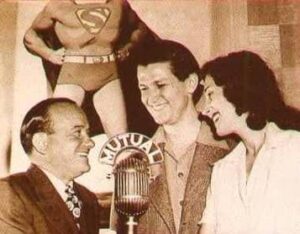

In the 1940s, the Adventures of Superman radio show brought him into American homes, where his soothing baritone foiled bank robbers, stopped train wrecks, and, in one famous arc, punched out the Ku Klux Klan. That 1946 storyline, Clan of the Fiery Cross, centers on a young Chinese-American boy facing racial prejudice after joining a neighborhood baseball team. Superman, of course, steps in to confront the group behind the harassment, a thinly veiled stand-in for the Klan.

In the 1940s, the Adventures of Superman radio show brought him into American homes, where his soothing baritone foiled bank robbers, stopped train wrecks, and, in one famous arc, punched out the Ku Klux Klan. That 1946 storyline, Clan of the Fiery Cross, centers on a young Chinese-American boy facing racial prejudice after joining a neighborhood baseball team. Superman, of course, steps in to confront the group behind the harassment, a thinly veiled stand-in for the Klan.

Legend has it that behind the scenes, activist and folklorist Stetson Kennedy had infiltrated the KKK and then provided the show’s producers with authentic code words, rituals, and organizational details to work into the script. The question remains over just how secret some of them really were, but when they were broadcast on national radio, they helped turn the Klan’s secrecy against them. It was a blow to the once-feared “invisible empire,” whose mystique was already steadily waning. Membership numbers dropped, and the Klan was pushed further underground.

Here, again, was Superman’s soft power: He had no problem socking racists in the jaw, but he also undermined their entire mythology. It was one of the earliest and clearest examples of Superman as a literal warrior for social justice, and proof that sometimes a righteous idea is stronger than a Kryptonian fist.

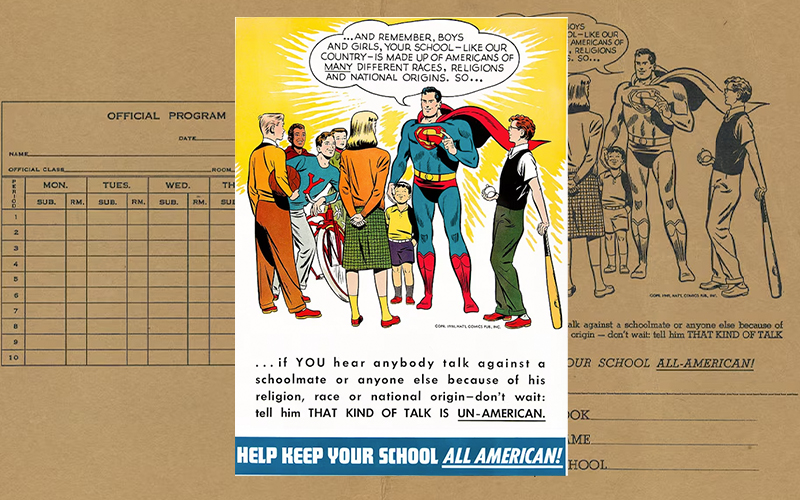

As if to serve as a reminder, an early 1950s illustrated poster (above) occasionally resurfaces on social media. In it, Superman stands before a group of kids and delivers a firm yet friendly lesson about respecting diversity. It looks like your standard bit of wholesome Americana — truth, justice, civics class vibes, and such, but its online efficacy shows how everything old is new again, including bigotry and xenophobia. The image first appeared in 1949 as a brown paper school book cover distributed to classrooms across America by the Institute for American Democracy, and the art is believed to be by Superman legend Wayne Boring (though the words themselves remain uncredited).

For years, it was a nearly forgotten chapter in Superman’s legacy. Still, it underscores that from the beginning, Superman stood for fairness – and, occasionally, for protecting your math book.

Star-spangled spandex

Following World War II, as the Iron Curtain descended abroad and McCarthyism rose at home, the Man of Steel continued to evolve with the times. The 1950s were an age of atomic anxiety and uniquely buttoned-up patriotism, and so Superman’s focus predictably expanded from truth and justice to also fighting for “the American Way.”

Following World War II, as the Iron Curtain descended abroad and McCarthyism rose at home, the Man of Steel continued to evolve with the times. The 1950s were an age of atomic anxiety and uniquely buttoned-up patriotism, and so Superman’s focus predictably expanded from truth and justice to also fighting for “the American Way.”

Nowhere was this more evident than in the 1952 Adventures of Superman TV series, which gave us George Reeves in tights and that now-iconic phrase. This version of the Man of Steel was clean-cut, trustworthy, and always morally upright; less a rebellious folk hero and more a civic role model. He wasn’t knocking down slumlords anymore; instead, he was teaching kids to look both ways before crossing the street and report communists to their local PTA.

The show’s tone was a blend of Father Knows Best and Punching Crime Straight in the Face. Superman’s invulnerability, a product of his yellow-sun-derived alien powers, came to symbolize the perceived strength and unshakability of the American system itself. You could practically see the bald eagle soaring overhead, a majestic tear trickling from its right eye, every time Reeves adjusted his cape.

It was during this period that Superman began to serve as a vehicle for American values in the ideological contest with Soviet-style communism. Fighting for “truth, justice, and the American way” was a nightly reassurance that good guys wore capes, believed in democracy, and would have definitely passed a background check. In a world newly divided between East and West, the Man of Tomorrow was powerful, benevolent, incorruptible, and, crucially, not government-controlled (for an alternate history of that scenario, might we suggest Mark Millar’s Superman: Red Son, which presupposes baby Kal-El landed in the Soviet Union, not Kansas). A superpowered metaphor for American exceptionalism, beamed directly into living rooms coast to coast, helped to tuck in an anxious nation every night with the promise that everything would be OK as long as Clark Kent was on the job.

Absolute power? Absolutely

Cold War tensions were on the rise, and so, not coincidentally, Superman’s power levels also went super-super-duper. By the 1970s, our boy in blue could juggle planets, sneeze away galaxies, and probably win a bakeoff while blindfolded. He developed super-hypnosis (because why not?), X-ray vision that could see through everything except lead and narrative tension, as well as the ability to travel through time and different dimensions.

Cold War tensions were on the rise, and so, not coincidentally, Superman’s power levels also went super-super-duper. By the 1970s, our boy in blue could juggle planets, sneeze away galaxies, and probably win a bakeoff while blindfolded. He developed super-hypnosis (because why not?), X-ray vision that could see through everything except lead and narrative tension, as well as the ability to travel through time and different dimensions.

At some point, it became less “Superman” and more “God with a day job.” Which is great for stopping meteors, less great for maintaining dramatic stakes. With an all-powerful sun god at their disposal, DC’s writers were left with a problem: How do you challenge a guy who can do literally everything except feel fear?

It wasn’t until a 1986 comics reboot, The Man of Steel by John Byrne, that brought Clark Kent back down to Earth (emotionally, if not gravitationally). Byrne’s Supes still packed a punch, but now he had vulnerabilities of the heart: loneliness, guilt, the crushing weight of responsibility, and Midwestern modesty. You know, relatable sensitive ’80s male stuff. Suddenly, the man who could change the orbits and rotations of planets was second-guessing himself at dinner parties.

Popcorn, pathos, and punches

Because most Americans voraciously watch movies and do not voraciously read comics, the image most U.S. adults still have of Superman is of this guy. In 1978, the Big Red S was due for his silver screen debut, and Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie gave us a timeless classic. S:TM introduced Christopher Reeve’s charming Kal-El, a goosebumps-inducing John Williams score, and that unforgettable tagline: You’ll believe a man can fly. Reeve’s Superman was warm, humble, and in possession of a jawline that could cut glass. He was a Big Blue Boy Scout in a time of post-Watergate disillusionment.

Because most Americans voraciously watch movies and do not voraciously read comics, the image most U.S. adults still have of Superman is of this guy. In 1978, the Big Red S was due for his silver screen debut, and Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie gave us a timeless classic. S:TM introduced Christopher Reeve’s charming Kal-El, a goosebumps-inducing John Williams score, and that unforgettable tagline: You’ll believe a man can fly. Reeve’s Superman was warm, humble, and in possession of a jawline that could cut glass. He was a Big Blue Boy Scout in a time of post-Watergate disillusionment.

But as America grew more cynical, so did our hero’s tone. Bryan Singer’s Superman Returns in 2006 tried to bottle Reeve’s old-school optimism but ended up as a searching, post-9/11 nostalgia soup. Then, Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel (2013) gave us a darker and grittier character, the type of Superman who stares mournfully into the distance while standing in the rain (at one point, he’s even wearing a Kansas City Royals t-shirt, which is enough to bring even the most optimistic of sports fans to heel). Some critics, noting the similar bleak tone as Christopher Nolan‘s Batman movies, dubbed the film The Clark Knight.

The character had been reintroduced as part of a larger project – assembling key Justice League characters to take full advantage of The Age of Superhero Blockbusters – and frankly, this version of Supes wasn’t entirely sure if humanity was worth saving. Neither were some moviegoers after the film’s final battle left Metropolis looking like a deleted scene from Independence Day. Half of Super-Fandom clutched their pearls; the other half asked, “Meh, why shouldn’t a Millennial Superman be sad and smashy?”

A return to (immigrant) roots

In more recent years, comic writers began poking around Superman’s attic and rediscovering his early essence – the immigrant farm boy with a moral compass more powerful than a locomotive. Comics like Superman Smashes the Klan (2019), written by Gene Luen Yang, were a lovely callback to the 1940s radio serial while leaning into the hero’s outsider status. It also reclaimed his role as a defender of the marginalized (though punching Klan members has never gone out of style).

Writers like Grant Morrison and Mark Waid presented a jeans-and-T-shirt Superman who could lift tractors and also everyday people, especially those being trampled by the system. These were stories about decency, humility, and putting others first, kind of a Ted Lasso who can bench-press buses. As it turns out, the most radical thing a superhero could be in the 21st century is … nice.

Which brings us to James Gunn, the man who made you cry over a sentient tree and a talking raccoon. He’s called Superman “an immigrant story,” and yes, people on the internet are already mad about that.

But in Gunn’s eyes, Superman isn’t here to be a god or a global cop. He’s here to be good. In a world spinning ever faster toward cynicism, fear, and extremely online arguments, Gunn’s Superman floats above it all with compassion. He’s not fighting for “America First” but for the American Best, that old-school ideal of helping your neighbor and standing up for those who can’t stand on their own.

Over nearly nine decades, Superman has been whatever America needed him to be: a fist or a flag, a dream or a doubt. During the Great Depression, he was a brawler for justice. Throughout the Cold War, a flying ad for American exceptionalism. During times of fear, a stoic symbol of security and safety. And in moments of reflection, a lonely alien just trying to do the right thing. He began as an outsider and became as American as apple pie, and now, he’s circling back to remind us who we are when we’re at our best.

So grab some popcorn, cheer when Lex Luthor gets pancaked, and whoop it up when that iconic red cape becomes a blur as it hits supersonic speeds. Then, when the credits roll and the lights come up, ask yourself: What does Superman mean now? Because he’s back and he’s challenging us, hoping we’ve still got enough humanity in us to rise to the occasion. Up, up – and away!