The flag of the United States – Old Glory, the Stars and Stripes, the Star-Spangled Banner – is more than just another of the 200 or so national banners around the globe. It’s a worldwide symbol that has inspired songs, poems, holidays, book volumes, art, and, well, everything in between. For centuries, its beauty has been in the eye of the beholder: It’s simultaneously been a powerful sign of nationalism and pride; an enduring signal of triumph, dignity, or joy; or even an urgent political statement raised in rebellion, support, or protest. It also has become the subject of myths, movements, and sure, even a misunderstanding or two.

Let’s run it up the flagpole, shall we?

No stars, just stripes

One of the earliest recognizable uses of red-and-white stripes on an American standard was on the so-called “Sons of Liberty” flag. The Sons were the original badasses of the American Revolution; many of the men who made up the clandestine political organization that pulled off the Boston Tea Party, in fact, began agitating the British as far back as 1765. That’s when nine Bostonians began rallying and funding large crowds of colonists to protest the Stamp Act.

Those men – John Avery, Henry Bass, Thomas Chase, Stephen Cleverly, Thomas Crafts, Benjamin Edes, Joseph Field, John Smith, and George Trott – became known as the Loyal Nine. All of them went on to become active members of the Sons of Liberty, and the nine vertical stripes on the Sons of Liberty Flag were a nod to these men.

The flag – of course – was eventually outlawed by the Crown. But the clever colonists simply switched the stripes to horizontal and kept on keepin’ on. Eventually, more stripes were added to represent all 13 colonies.

Heavens to Betsy

The 1770s were a revolutionary time of rapid change in America, but you couldn’t just stroll into Walmart and pick up a flag. Back then, flags were most often created by an upholsterer upon request. This is where the legend of Betsy Ross emerges. Ross, an upholsterer who had made flags for the Pennsylvania navy, is widely mythologized as the person behind the “first” U.S. flag. We even call that first star-spangled banner – with its ring of stars in a blue field – the “Betsy Ross flag.”

Here’s the rub, though: Ross, who died in 1836, was never recognized as the flag’s creator during her lifetime. Her story only entered the American consciousness in the 1870s after her grandson presented a research paper to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in which he claimed that his grandmother had “made with her hands the first flag” of the United States.

As the Ross family story goes, in the summer of 1776, George Washington, Robert Morris, and Betsy’s uncle George Ross met with her at her home in Philadelphia. They handed her a sketch of a square flag that featured 13 red-and-white stripes and 13 six-pointed stars in a blue field. Ross made slight modifications – she added another third of horizontal length, then arranged the stars in a circle and gave them five points instead of six. A flag bearing this exact description was officially adopted on June 14, 1777 – the first version of what has become one of the most enduring and iconic national standards in the history of the world. Pretty straightforward, right?

Lighten up, Francis

We now enter into evidence the esteemed gentleman from New Jersey, Francis Hopkinson. A delegate to the Second Continental Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Hopkinson also was a skilled flag-maker and designer – and, in many historians’ view, the creator of the first U.S. flag. Unlike Team Betsy, who make claims that Ross created the flag based on oral histories, Team Francis has receipts. Sort of.

In 1780, Hopkinson submitted an invoice to Congress that said in exchange for designing the “flag of the United States of America,” the nation owed him two casks of ale. Notes from the Continental Congress at the time suggest Hopkinson did indeed design the first flag, but because there are no pictures or written descriptions of it, and because Hopkinson also designed other flags, symbols, and seals for our young nation including our first Naval flag, we can’t know for sure what his original design looked like, exactly.

Regardless, the flag bearing the original circular star pattern is most often called The Betsy Ross Flag. The “Francis Hopkinson Flag” doesn’t have the same kind of homespun ring to it, anyway.

Hey now, you’re an all-star

By 1794, the United States was free and independent of Great Britain, sitting on a vast continental reserve, and expanding west. In other words, we weren’t going to stay at 13 states for long. When Vermont and Kentucky were admitted as the 14th and 15th states, respectively, no one knew definitively how to represent the new members of the American family. So Congress passed a new Flag Act, specifying the flag should have 15 stars (and, it should be noted here, that it’s this version that flew over Fort McHenry during the War of 1812, which inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner” and set it to an old English drinking song).

During this stretch, there were a lot of different iterations of the U.S. flag – always with 13 stripes per the 1794 Flag Act, but with many varying takes on the star pattern.

Congress wouldn’t pass another Flag Act until 1818, which finally established the current rule of having the number of stars match the current number of states. We should stop here to say that if you’re in possession of an American flag with 16 to 19 stars on it, it’s probably quite the commodity; between 1794 and 1818 there were no official U.S. flags with 16 (Tennessee), 17 (Ohio), 18 (Louisiana), or 19 stars (Indiana).

Having brought some mild order to the matter, Congress then did what it does best – nothing – as the nation continued to add states. Pretty soon, the flag began to swell with stars. And, because the 1818 Flag Act again failed to specify what pattern the stars should be arranged in, designs continued to vary across the land.

Finally, in 1912 President William Howard Taft established the pattern of stars that we know today, and the era of funky star patterns came to a quiet end. The 48-star, 49-star, and our current 50-star flag all dutifully conform to the orderly staggered-row pattern we all know so well today.

What’s in a nickname?

The American flag is often called Old Glory. The first flag to be known by that moniker was a 10-by-17-footer owned by William Driver. Born in Salem, Massachusetts, Driver was a sailor who eventually settled in Tennessee.

Driver more than likely named the flag when thinking back on his 20-year career as an American merchant seaman who sailed throughout the South Pacific. “It has ever been my staunch companion and protection,” he once wrote. “Savages and heathens, lowly and oppressed, hailed and welcomed it at the far end of the wide world. Then, why should it not be called Old Glory?”

Driver more than likely named the flag when thinking back on his 20-year career as an American merchant seaman who sailed throughout the South Pacific. “It has ever been my staunch companion and protection,” he once wrote. “Savages and heathens, lowly and oppressed, hailed and welcomed it at the far end of the wide world. Then, why should it not be called Old Glory?”

By 1837, Driver was widowed and so he moved his three children to Nashville to be closer to his two brothers. During the Civil War, Driver stayed loyal to the Union and sewed Old Glory into a quilt for safekeeping. When the Union army rolled into Nashville in 1862, Driver gave them Old Glory to fly over the Tennessee State Capitol for a time. Today, you can find Old Glory at the Smithsonian Museum of American History in Washington.

And our flag was still there

Our flag’s fluctuating history makes it a fertile space for producers of fiction (or even nonfiction) to tinker. Books, movies, and television shows have all offered up alternate or fictional future versions of the flag – often as a critique of American imperialism or commercialism. In the alternate history of HBO’s Watchmen (2019), the United States had claimed Vietnam as its 51st state back in 1985. The standard was redesigned with a centered, circular blue field.

Given that the show featured a naked blue man who was omnipotent and all-powerful and his super-genius friend who lived on a moon of Jupiter, this center-of-the-universe design seems fitting.

Speaking of those sweet-if-not-slightly-apocalypse-obsessed days of the 1980s: In 1987 ABC ran a mini-series called Amerika, a tale that presumed the Soviet Union had conquered and occupied the United States. Besides scaring the bejeebus out of a good share of the country, Amerika (filmed partly in Nebraska) also produced an iconic take on the flag: The hammer-and-sickle-besmirched banner of the Soviet United States of America.

Amerika really messed with viewers’ minds, using communist iconography as frightening reminders of what would happen if we gave an inch to the Evil Empire, as President Reagan referred to the USSR at the time. In Amerika’s second episode, red banners with images of Abraham Lincoln and V.I. Lenin were featured in a “Lincoln Week” parade in Omaha (parades in communist countries often used decorative banners bearing the likenesses of Communist leaders or “adopted” national heroes). I mean, we knew it was fiction, but seeing Lincoln and Lenin together on one banner was extremely jarring in 1980s Cold-War America.

Of course, by 1992 the USSR was crumbling and Old Glory suddenly represented the last remaining 20th-century superpower. But this is an essay about flags, not geopolitics, so let’s move on.

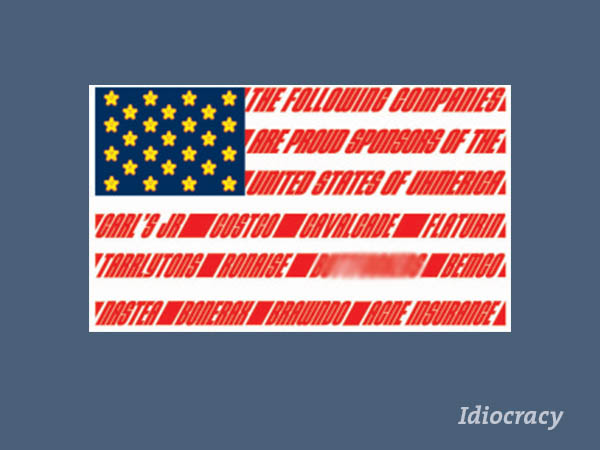

One of the strangest versions of our national flag – though, admittedly, one that has been continually referenced in recent years – is the U.S. flag in Idiocracy (2006). This time-traveling comedy features an “Uhmerica” of 2505, a dystopian (sorta) nation unimaginably dumbed-down by mass commercialism and mindless TV programming.

To fully grasp why Uhmerican flagmakers would add a series of tiny yellow Carl’s Jr. symbols in the canton plus the names of sponsors in the flag’s red stripes, you’ll have to just watch this cult classic. ‘Nuff said.

Codebreakers … or not

Much like those modest, reserved folks who have never read the Constitution beyond its first three words but who believe themselves to be Constitutional scholars, there is no shortage of experts regarding the U.S. Flag Code who often share dubious do’s and dont’s regarding our nation’s flag. Mostly, people rush to conflate the Flag Code with criminal law when confronted with something they might not like.

The examples are endless, but to cover the most-often cited ones, it’s not ‘illegal’ to:

Burn the flag in protest. Burning the American flag as a symbol of protest is certainly controversial, and often infuriating. While laws have been enacted making desecration of the American flag a crime in the past, the U.S. Supreme Court has struck those laws down, asserting that the First Amendment protects flag burning as symbolic speech. The most recent majority opinion, in 1990, said in part: “If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.”

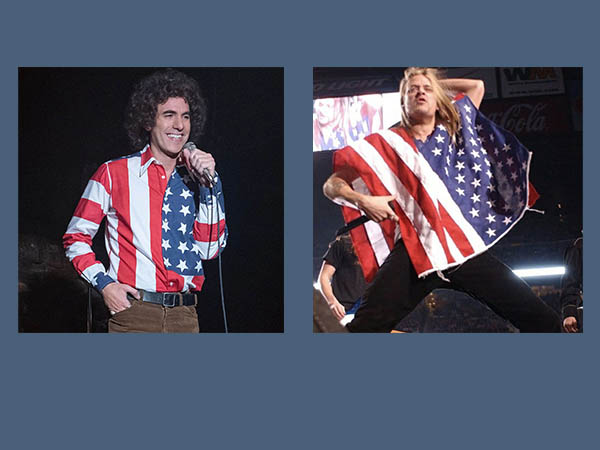

Wear a piece of clothing resembling the U.S. flag. The U.S. Flag Code clearly states that the flag should never be used as wearing apparel, bedding, or drapery. The recent upsurge in “flag fashion,” from shoes to shirts to swimming trunks, is out of step with the letter of the Flag Code (as is the use of the flag in advertising, on costumes or athletic uniforms, or anything that is for temporary use and intended to be thrown away. Why, then, are county jails not full of flagrant flag desecrators every July 4?

The main reason is that the Flag Code is a set of guidelines. Breaking them doesn’t mean you’re breaking the law, and you won’t hauled off in handcuffs (unless you’re Abbie Hoffman in 1968, natch). For better or worse, we give a lot of grace in modern America when it comes to this part of the Code. The prevailing opinion seems to be: It’s not necessarily about strict adherence to every line of the Code, but about one’s intent, and in most cases, that intent is to honor the ideals of the flag, not desecrate them.

There’s been one high-profile instance in recent memory where someone literally wore an American flag. At halftime of the 2004 Super Bowl, the inimitable Robert James Ritchie, a/k/a Kid Rock, paraded on stage in what appeared to be Old Glory. Lucky for Ritchie, then, that whatever nascent controversy that would have erupted was forgotten minutes later, when Janet Jackson and Justin Timberlake had their infamous “wardrobe malfunction.”

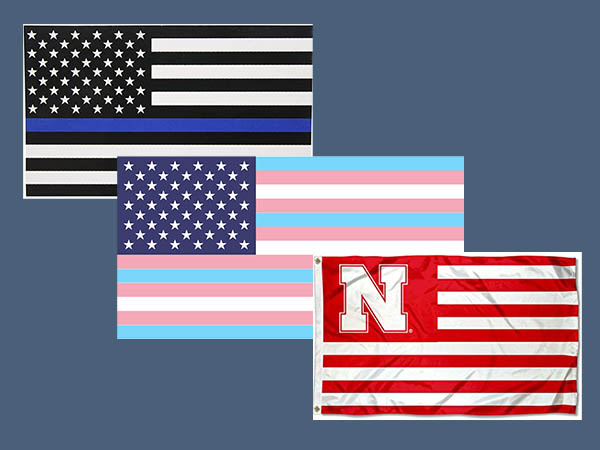

Display a differently-colored version of the flag. Multiple “takes” on Old Glory exist in our culture, making statements in support of a variety of causes. Depending on one’s point of view, they’re either soaringly inspiring or patently offensive. Those who drift toward the latter sometimes claim such flags are a violation of the U.S. Flag Code.

And yet, they’re not technically a violation. Such flags are not official American flags; they’re likenesses of the flag. And because of this fact, the Flag Code doesn’t technically apply (but, like star-spangled clothing, whether they’re in good taste is another matter. Maybe read the room first).

Time to retire?

There’s no official rule on when a ragged old flag should be disposed of, or “retired,” in official parlance. There are exceptions, but in general Americans tend to dislike the sight of a tattered or ragged national emblem still flying past its prime. The preferred way to retire an American flag is to burn it, with two big guidelines: (1) The action must be private and dignified, and (2) the flag must be burned completely down to ashes.