What’s an Article V convention?

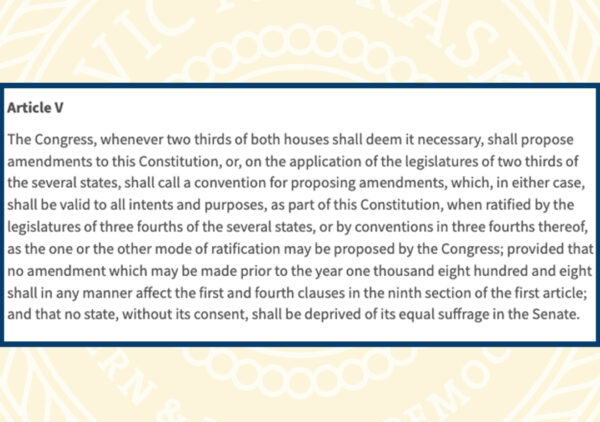

The Constitution can be amended in two ways. The only way we’ve used so far needs two-thirds of both houses of Congress to propose an amendment, which must then be ratified by three-fourths of states (presently, 38 states). This is almost always done by a simple vote of each state Legislature, though Congress required the twenty-first amendment (repeal of prohibition) to be ratified by state convention.

The Constitution can be amended in two ways. The only way we’ve used so far needs two-thirds of both houses of Congress to propose an amendment, which must then be ratified by three-fourths of states (presently, 38 states). This is almost always done by a simple vote of each state Legislature, though Congress required the twenty-first amendment (repeal of prohibition) to be ratified by state convention.

In the last decade, organizations of varying political affiliations have promoted the second way to amend the Constitution – a convention – to make changes that would be extremely unlikely to make it through Congress. There is a substantial effort among progressive activists, namely Wolf-PAC, to call a convention to pass an amendment to overturn Citizens United. Wolf-PAC has passed its application resolution in five states.

The more active and imminent effort is by the Convention of States Action, a group led by conservative activist and Tea Party Patriots co-founder Mark Meckler. Convention of States Action, or COSaction, supports a call to convention to:

- Impose fiscal restraints on the federal government;

- Limit the power and jurisdiction of the federal government; and

- Limit the terms of office for its officials and for members of Congress.

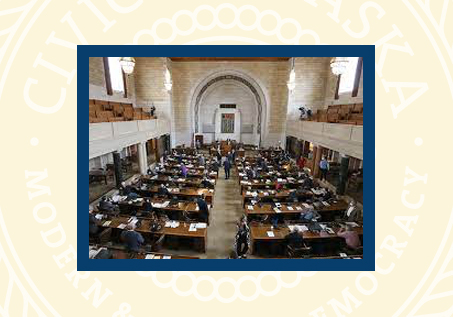

COSAction has successfully passed its resolution in 15 states, with active legislation in all but eight states. COSAction legislation has been repeatedly introduced in Nebraska. It is consistently defeated by a bipartisan group of senators with a range of concerns, from devastating effects on our state’s budget to unpredictable outcomes with the Constitution.

What does an Article V convention have to do with voting rights?

In short, it can strip the Department of Justice of its powers and standing to enforce voting rights.

The amendments proposed within the scope of a COSAction-style convention could expose federal voting protections to political sabotage and retribution by jeopardizing the capacity and authority, if not the very existence, of the Department of Justice.

While states have broad authority to administer their own elections, they are bound by certain baseline rules and protections designed to provide an at least somewhat uniform, accessible experience for all eligible voters. Some of these protections are enshrined in the Constitution in the fifteenth, nineteenth, twenty-fourth, and twenty-sixth amendments, but most of them come from four pieces of federal legislation – the Voting Rights Act of 1965, The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act of 1986, The National Voter Registration Act of 1993, and the Help America Vote Act of 2002. All of these provisions are enforced by the Voting Section of the Department of Justice.

While states have broad authority to administer their own elections, they are bound by certain baseline rules and protections designed to provide an at least somewhat uniform, accessible experience for all eligible voters. Some of these protections are enshrined in the Constitution in the fifteenth, nineteenth, twenty-fourth, and twenty-sixth amendments, but most of them come from four pieces of federal legislation – the Voting Rights Act of 1965, The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act of 1986, The National Voter Registration Act of 1993, and the Help America Vote Act of 2002. All of these provisions are enforced by the Voting Section of the Department of Justice.

When a state violates one of the protections outlined in these laws, the Department of Justice is the office responsible for intervening. The DOJ is voters’ last line of defense against state infringement of voting rights. The DOJ’s capacity and authority to challenge voting restrictions are directly threatened by the second plank of the COSAction legislation: “Limit the power and jurisdiction of the federal government.”

There is no restriction, consolidation, or elimination of a federal agency not included under this broad call to action. Restricting the DOJ’s authority to protect voters against a state legislature’s restriction, reducing the voting section to hamper its efficacy, or eliminating the voting section entirely would be entirely within the scope of this “limited” call to a convention.

The current political climate and the results of a simulated convention in 2016 raise the possibility of grave consequences for voting rights.

When we began work on this issue in 2016, it was defending against a bad hypothetical. Today, with the national rhetoric surrounding voting and elections increasingly venomous, it is easy to imagine amendments written, funded, and promulgated by the toxic and well-funded politicians and D.C. strategists determined to erode public trust and participation in our elections.We have no doubt that much of the grassroots support for an Article V convention is driven by genuine, well-intentioned concerns about the national debt or perceived government overreach. But those intentions don’t stand a chance against the political and financial forces waiting to capitalize on this opportunity. The well-meaning objectives of grassroots supporters will be ignored entirely or accommodated, co-opted, and exploited to make anti-voting efforts even more powerful.

Our concerns about a COSAction call for a convention were validated by the organization’s simulated convention, in which legislators from all 50 states gathered in Colonial Williamsburg in 2016 to debate and advance mock-proposals to get a sense of how a convention would work and the kinds of proposals it might advance. The simulated convention, hailed as “a complete success” by COSAction, advanced the following proposals:

Our concerns about a COSAction call for a convention were validated by the organization’s simulated convention, in which legislators from all 50 states gathered in Colonial Williamsburg in 2016 to debate and advance mock-proposals to get a sense of how a convention would work and the kinds of proposals it might advance. The simulated convention, hailed as “a complete success” by COSAction, advanced the following proposals:

- Raising the debt ceiling will require a two-thirds vote of both houses of Congress;

- Limit Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce;

- Term limits on both houses of Congress;

- Give the states the power to rescind federal laws and regulations with three-fifths ratification;

- Eliminate all taxes on income, gifts, and estates and require a three-fifths majority in both houses to enact any federal taxes; and

- Allow Congress to repeal any federal regulation unless a majority of both houses vote to affirm or adopt the regulation.

From a voting rights perspective, Nos. 4 and 6 are particularly troubling. Giving three-fifths of states the power to rescind federal law, including the aforementioned legislation providing the bulk of our election rules and protections, is a bad, dangerous policy. This could allow national protections to be rescinded by less than one-fourth of the population.

For example, if the 30 least populous states and the District of Columbia all ratified the repeal of the Voting Rights Act, those states would represent a population of 79,538,370 or just 24 percent of the U.S. population. Meanwhile, the states representing the remaining 248,492,951, or 76 percent of the population, would be overruled. We cannot allow federal protections for voting rights to be dictated by 24 percent of the population.

No. 6 – allowing Congress to repeal any federal legislation unless a majority of both houses affirm it – is equally unacceptable. This would make federal protections of voting rights especially vulnerable to the political whims of Congress. A slight majority in one chamber by one party should not jeopardize baseline federal protections.

This is a real threat.

Supporters of an Article V convention tout the high ratification threshold – three-fourths of states – as protection against any highly controversial proposals becoming law. This argument relies on either misinformed or blatantly deceitful assertions that the state’s voters will have a direct impact on a state’s decision to ratify.

Constitutional amendments are almost always ratified by an up-or-down vote of state Legislatures. Each state can create its own rules for ratification as long as they don’t interfere with the Article V process. Most states, including Nebraska, treat ratification of amendments to the U.S. Constitution just like any other resolution or bill, requiring a simple majority vote to affirm. The only other method is a state convention, which can also exclude the majority of voters from the process.

Constitutional amendments are almost always ratified by an up-or-down vote of state Legislatures. Each state can create its own rules for ratification as long as they don’t interfere with the Article V process. Most states, including Nebraska, treat ratification of amendments to the U.S. Constitution just like any other resolution or bill, requiring a simple majority vote to affirm. The only other method is a state convention, which can also exclude the majority of voters from the process.

It is dangerously naive to assume that a process as high-stakes as an Article V convention can be safeguarded by the moral fortitude of 13 state Legislatures or state conventions. Our most representative measure of “the will of the people” – a statewide vote – is completely absent from the amendment-ratification process.

There are many reasons beyond endangering basic voting rights why Nebraskans should oppose LR14. But the danger to voting rights via such an untested process is urgent.

Eliminating or rendering useless the Department of Justice, voters’ last line of defense against state infringement of voting rights, is entirely within the “limited” scope of a COSAction-style call for a convention. Such a proposal could emerge under a number of guises, from “reducing spending” to “limiting government overreach,” and could be advanced from the convention and ratified by three-fourths of state legislatures despite opposition from a majority of voters. The simulated convention supports these concerns, and the current political climate around voting makes this a singularly bad time to expose our election protections.

We should not – and must not – add Nebraska’s name to this dangerous and untested idea.

Westin Miller is Director of Public Policy at Civic Nebraska.